Transatlantic Foreign and Security policy

In discussions on transatlantic foreign and security policy, Keeping Channels Open has engaged with dozens of stakeholders on the global challenges erupting daily and the deficits in Western strategy and solidarity.

Against the backdrop of turbulence caused by the Ukraine War, Brexit, Trump, COVID, the Afghan withdrawal and other watershed moments, we are discussing how to shore up vulnerabilities in cross-border cooperation, democratic solidarity, health systems, energy and food supplies and economic inter-dependence.

Topics range across effective ways to end Russia’s aggression and hybrid threats, tackle future pandemics and climate change, strengthen liberal democracy against authoritarianism and interference, engage effectively with China and reshape the global world order.

Our Questions

- How do we stop Russia’s war on Ukraine and spillover effects in the broader region?

- How dangerous are current nuclear threats, including from Iran, North Korea and Russia?

- How do we capitalise on Western unity to boost resilience and security in multiple domains?

- Is the war in Ukraine and other crises forcing geopolitical realignment?

- Do we need new security and economic architecture to deal with new challenges?

- Will recent positive UK-EU cooperation spread to other areas of foreign policy and security?

- Will commitments on climate change and multilateral reform be lost amidst new economic and security crises?

- Is America truly ‘back’ or is there a need for more European ‘strategic autonomy’?

- Is the Western appetite for conflict resolution gone, after withdrawals from Afghanistan, Syria, and other conflict zones?

- Are red lines on China tough enough, while still leaving room for engagement?

- How can liberal democracies come together to defend our values and strengthen rules-based systems in the face of technological change, rising authoritarianism, populism and disinformation?

- How do we win the battle for public hearts and minds against disrupters exploiting cost-of-living crises, migration, and disinformation? How can we restore concepts of inclusive democracy and fact-based productive debate?

To debate these tough questions, we welcomed the views of analysts, think-tanks, politicians and civil servants, including from the US Administration, EU, NATO and UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office.

Renewing the Transatlantic Alliance

& Values-based Multilateralism

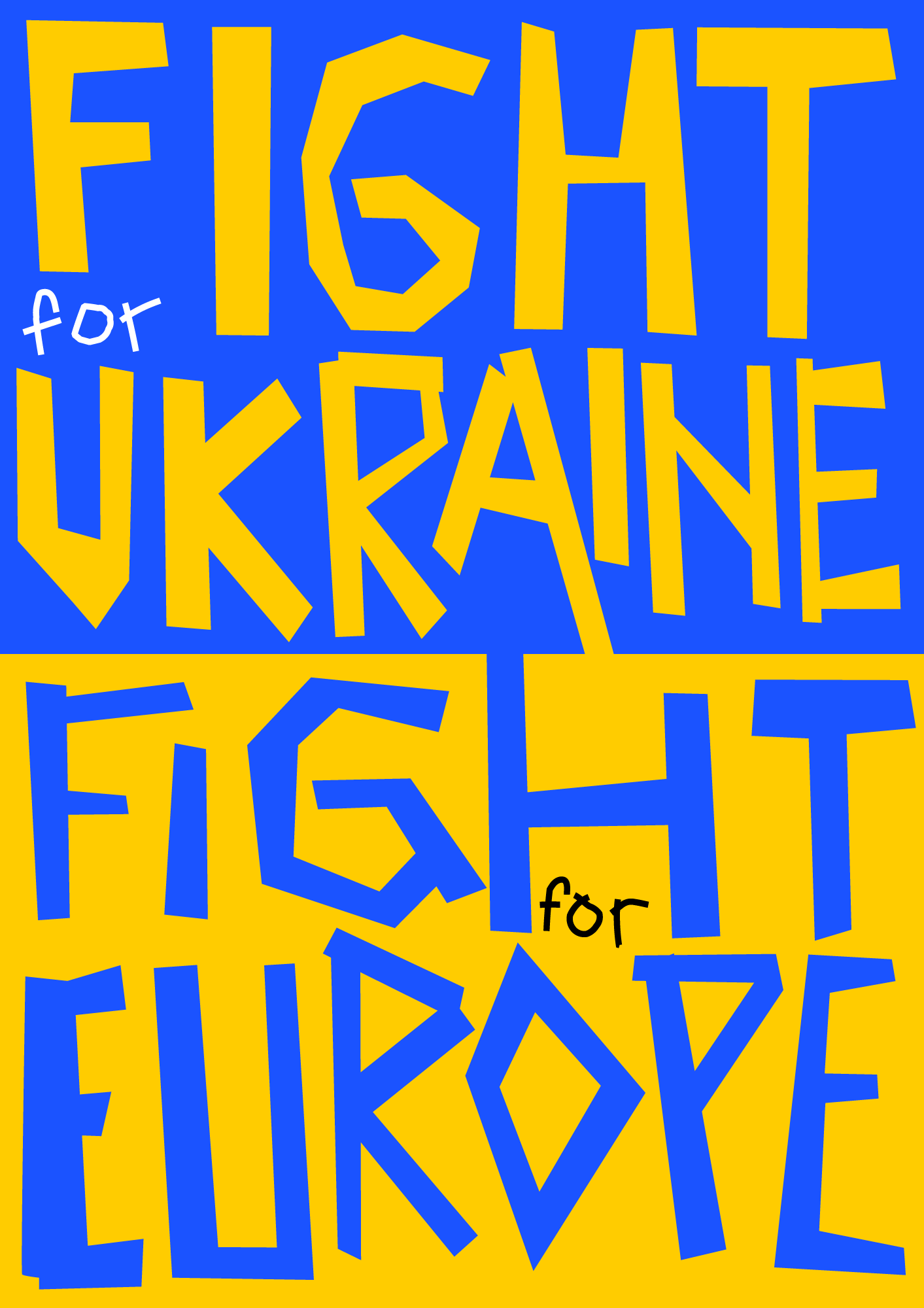

russian invasion of ukraine

In 2022-23, we held group discussions with UK, EU and US politicians and experts on how to coordinate an array of responses to the Russian war. Many stakeholders agreed that the invasion reflected a culmination of Putin’s hybrid aggressions in the region since 2008 aimed at expanding Russia’s empire, undermining Western democracies and cementing his power.

The West had not been not tough enough with sanctions and other measures after the annexation of Crimea in 2014, incursions into Eastern Ukraine, Syrian bombardments, occupation of parts of Georgia, downing of the Malaysian airliner and so on. However, there was no green light given to Putin to invade Ukraine – the aggressor must be the focus of blame.

Despite a highly praised Ukrainian fightback, the Russian army have consolidated positions in the East and South and imposed a blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports, wreaking havoc on the world’s wheat supplies.

Read more

Russia v Ukraine: what’s at stake

A selection of expert comments…

“This is a turning point. We can be grateful to Putin for having jolted us all out of complacency, but we mustn’t take our eye off the ball. We have to collectively do the hard graft to wean ourselves off oligarch money, not just from Russia but from Central Asia and elsewhere. We must also build up our resilience in all areas including cybersecurity, democracy & disinformation & secure our energy independence.”

“The war in Ukraine is definitely about democracy, particularly at Putin’s borders; this is what he fears. Of course, it’s also about reclaiming a lost Russian Empire and fears of waning global influence. But at its core, it is about the fear of the contagion of democracy. The biggest threat to Putin’s security is democrats within.”

Read more

Investigating War Crimes in Ukraine

A selection of expert comments…

“Russia’s unlawful behaviour did not start in February 2022. They have been committing war crimes and violating international law since early 2014. Unfortunately, there has been no proper legal answer to these questions by any international judicial institutions.”

“This will be the most documented conflict in history and the most intensively examined commission of war crimes in the shortest period of time.”

“The trials in Ukraine are sending a very clear message that we respect the rule of law and that every soldier who comes to Ukraine and commits war crimes will face justice.”

Read more

Geopolitical Shifts

Most participants in recent discussions agreed that the world has radically changed in recent years through a reapportionment of power and influence.

“This change in the balance of powers has been caused by an increasingly assertive China, growing India and Indonesia, revanchist Russia and deep divisions in the democratic world.”

“The perceived failures of costly interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan have put the US and Western allies on the backfoot. Public sentiment will deter them from similar large-scale missions in future.”

Read more

Afghanistan

The messy withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021 marked a watershed moment in Western interventionism. Based on unilateral US decision-making, the move sent a strong signal about transatlantic disunity and the abdication of a leading US role in conflict resolution. As Afghanistan haemorrhages more refugees and further restricts the freedoms of the female population, its future hangs in the balance.

New instruments, tools and formats will be needed to advance values overseas and resolve conflicts, since comprehensive nation-building missions are no longer in vogue. There will also be a focus on shoring up liberal democracy at home and linking foreign and domestic policies, in order to win over weary and sceptical publics.

Read more

Forging Common Agendas

Overall, participants have been encouraged that the Western alliance appeared to be coming together on a common agenda after a spate of serious crises.

“We’ve got the big issues on the table of our top institutions, and are having a dialogue on the most important items.”

Read more

recommendations

- Develop an agenda of democratic resilience and speak with a collective voice on good governance and human rights violations overseas. Tangible commitments can be made through the UN, G20 and Democracy Summit and in cooperation with Indo-Pacific democracies.

Read more

Briefing Papers

A summary of some of our roundtables held under the Chatham House Rule, including top comments from European, American, British and Australian politicians, experts and analysts.